The Geheime Staatspolizei, or the "Secret State Police” was codified into German law by the Nazi Reichstag on February 10, 1936. The Reichstag was Germany’s Parliament which, by passing this law, gave Germany’s secret police the legal authority to operate outside of the legal system. The Gestapo, as this law enforcement agency is known, now had the power to take essentially any action against those they perceived as enemies of the state. Those actions included detentions, interrogations and arrests of anyone they deemed subversive of the Nazi regime, even if evidence was scant or non-existent. The passing of the “Gestapo Law” essentially elevated the Gestapo above any other judicial mechanism in Germany.

The new law also gave the secret police full control over the suppression of political opposition. Since the Gestapo could take legal action, such as making arrests, even for perceived incredulities against the Nazi regime, their legal authority to suppress political opposition further made it one of the most feared and powerful organizations in the country. The Gestapo had a vast network of informers which they relied on to illicit information about dissenters or other “undesirables.” The law would remain in effect until the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945 and is still viewed as a key piece of legislation which permitted the regime to control the German people.

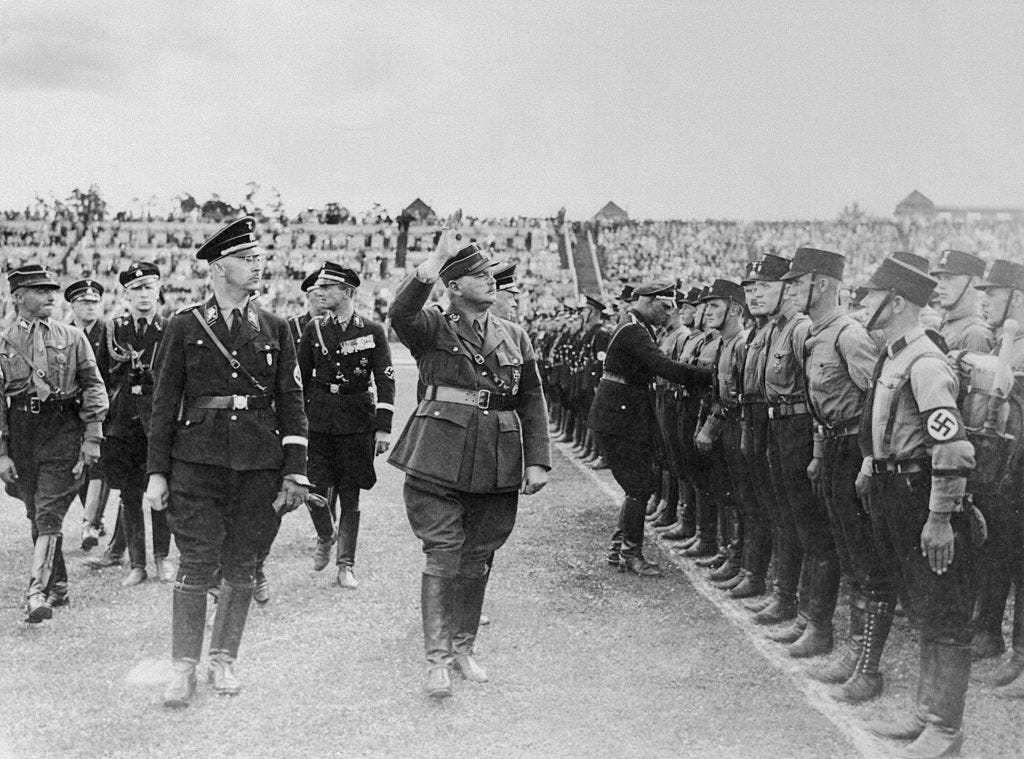

Who were the Gestapo? Many will know the names of prominent Gestapo figures such as Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler, but it was the thousands of Gestapo officers and informants who carried out, or otherwise enabled, the atrocities that would later be judged at the International Military Tribunal at Nürnberg. The roots of the Gestapo are traced to the civilian police force in Prussia, which at the time was Germany’s most prominent state. In 1932, following an internal purge, the Prussian police force removed from duty anyone even suspected of having sympathy for left-wing politics or Jews.

Thus, shortly before Hitler became chancellor in early 1933, the police force of Germany’s largest state was already primed for a radical transformation. After Hitler’s ascension, Göring, who was minister of the interior of Prussia, reorganized the Prussian police force by separating the political and espionage units from the rest of the police force. He then filled those units with thousands of Nazi’s and placed them under his personal command as the Gestapo on April 26, 1933. Himmler, then head of the SS, was taking similar action at the same time. Along with Heydrich, they reorganized the police of the rest of Germany, and in April of 1934 Himmler was given command over all of the Gestapo.

The majority of those comprising the Gestapo were police officers trained in the requisite law enforcement and intelligence gathering methods of the time. They carried out the daily operations such as the aforementioned arrests and interrogations, as well as surveillance of anyone deemed to be a threat to the Nazi state. Historian Frank McDonough, who authored The Gestapo, contends that at no time did the Gestapo have more than 16,000 full time officers. However, that number has been alleged to be closer to 40,000 and up to 150,000 if including informants and other personnel aside from the law enforcement officers.

McDonough argues that the Gestapo officers who attained sought after positions were chosen because of their law enforcement training and experience, and not because they were members of the Nazi Party. His book is based off of 73,000 Gestapo documents that survived the war, so there is little doubt that he comes from a place of knowledge on the subject, and that knowledge has led to a different perspective on the Gestapo than other historians have brought to light. McDonough points out that most of the Gestapo officers who joined the Nazi Party only did so to keep their jobs and gain their pension in retirement.

Some would argue that the ends don’t justify the means. A lucrative pension upon retiring is something just about anyone would like to have. But, that doesn't mean you betray your countryfolk to obtain it, or swear allegiance to a regime you don’t actually support to obtain it. Or do you, in order to affect your small piece of the puzzle and limit the detriment that is caused to the people you encounter on a daily basis? It seems that most people think they would be an Oskar Schindler type of person, taking great personal risk to help those society was willing to send to death camps, but in reality the vast majority would simply toe the line and become a Nazi, or feign becoming one. Remember, those lucrative pensions are hard to come by after all.

If the Nazi analogy is too difficult a hurdle to get over, what about the US soldiers involved in the My Lai Massacre of the Vietnam War or in the Kill Team of the Afghanistan War? Or are examples like these too far beyond the pale because they involve murder, whether it be by Gestapo agents during the WWII era or US soldiers during the Vietnam and Afghan wars? Is murder the supposed hardline for everyone? It wasn’t for many involved in the Nazi regime, or for those US military examples. There are countless examples from history we can turn to, but it seems like history often has a way of repeating itself or at least going through stages that are eerily similar to the past. Aren’t we supposed to learn from history so we don’t make the same mistakes?

This week, it was reported that the FBI published an intelligence product aimed at expanding its informant base by targeting the Catholic Church. The FBI report indicated that it was believed white supremacy has found a home in the Catholic Church, particularly amongst those devout worshippers who prefer the traditional Latin mass. The FBI labels these Catholics as “Radical Traditional Catholics” (RTCs) and makes the leap in logic that white supremacists “will continue to find RTC ideology attractive and will continue to attempt to connect with RTC adherents.”

Their basis for such a claim? Relying “on the key assumption” [emphasis added] that white supremacists would remain attracted to RTC ideology. Where’d they come up with that assumption, or is it simply based on their belief that “RTCs” have been deemed subversive of the regime; even if such a claim or assumption is inaccurate? Nonetheless, the FBI Richmond office published that product and it was even signed off by the highest ranking lawyer in the Richmond office. So, even after review by those who did not write it, the final legal ruling was that this was good to go in the FBI’s view. How is this any different than the Red Raids or treatment of civil rights leaders that have been written about on this substack, and most certainly where we have only begun to scratch the surface with the history of the FBI and other governmental forces.

This article says in the headline that FBI headquarters “disavows” the RTC intel product. Are they only disavowing it because it was brought into the public domain? Or is it because they actual believe it was problematic? If they believed it was problematic, why did the highest ranking FBI lawyer in the Richmond Division approve such a product? If that lawyer deemed this type of informant recruiting measure appropriate, how many other lawyers, agents, executive staff and other employees in the FBI think it’s appropriate? If it is appropriate for the Catholic faith, there certainly are similar like mechanisms that the FBI can endeavor into with other Christian based faiths and all other religions too.

Increasing the informant base is, after all, what one of the main tenets of that RTC intel product was intended for. The product refers to this as “source development.” The FBI maintains a source pool, or CHS base, of an untold number. They keep the number of CHSs they have a secret from the American people because they are actively using them against you; and in fairness against actual enemies of the United States and in criminal cases where it can be a legitimate tool. Many of those CHSs have been attached to the FBI’s hip for five years or longer and the FBI pays them, with tax payer dollars, to the tune of $42 million a year. Law enforcement agencies do have some legitimate purposes for having and utilizing informants. Is creating a source base out of the Catholic Church, or any faith based organization, congruent to those legitimate purposes? With FBI HQ suddenly disavowing the intel product after it hit the public sphere, we all can begin to decide for ourselves what the answer is.

What does a nation do when their laws become unjust and opposed to the very people they are supposed to protect? The below video is recent. December of 2022. The officers involved continually say they are just doing their job. Just doing what they are told. That they have a lawful order. Well, the Gestapo Law made it lawful for that police agency to terrorize people, even up to death and sending them to concentration camps. Many will argue, “this isn’t the same thing.” Maybe not. But, it’s at least a debate worth having. The Gestapo didn’t start off by killing people or sending them to concentration camps either. That came with time as their power increased and the collective voice of the people was shattered.

The cops above are doing their job because they justify the orders they receive in order to continue receiving that direct deposit every two weeks leading towards that pension which will eventually come; as long as they simply do what they are told. What about the business owner that they are legally shutting down two years after that business owner defied a mandate (not a law) to shut down? That business owner had to shut down but Wal-Mart didn’t, and now, since they defied that mandate, they are being forced to close years later. At Nürnberg many Nazis, undoubtedly including Gestapo law enforcement officers, used what became known as the “Nürnberg defense.” This line of defense is also known as the “superior orders plea.” This type of defense, if you’re comfortable calling it that, argues that someone should not be considered guilty of anything that was ordered by a higher ranking official, whether they be a higher ranking military officer or other governmental official. That defense did not work at Nürnberg.

Prior to the end of WWII, the Gestapo operated legally too. No doubt people will cast aspersions about this comparison, but again, it is a comparison worth making. What became known as the Gestapo didn’t start with concentration camps, brutal interrogations, or arrests based on dubious evidence. The Gestapo did gather a wide range of information on its citizens though, and develop an informant pool from those citizens. The Gestapo collected information pertaining to political views and affiliations, religious beliefs, personal habits and behavior, professional and financial information, and anything their informants provided.

When the Prussian police force began “reforming” in the early 1930’s, was anyone speaking out? Were there law enforcement officers then who were proverbially blowing the whistle before those changes took full effect? If the answer is yes, what happened to them? Were they allowed to stay in their career and get that pension? These questions, and more, are worth investigating for history’s sake, and worth asking for our own.

Postscript

This week’s edition is a bit shorter than last week, which honestly kept going and going as I researched it. For those of you who are still reading, thank you. I appreciate your viewership and I hope I am providing something worthwhile. I’m still trying to figure out what this substack is, and is going to be. By all means, I am open to ideas. Are the posts too long, too short (doubtful), in need of a different approach, etc.? I had to travel this week, and in preparation for that and then being gone, did not have as much time to organize my thoughts as usual. I know I posed a lot of questions this week. By all means feel free to answer some of them in the comments. Instead of going down every rabbit hole I wanted to, I was forced to limit it this week, so I hope there is at least some food for thought here to digest. I didn’t even get into the Reichstag fire either, and only touched on the Gestapo’s informant campaign.